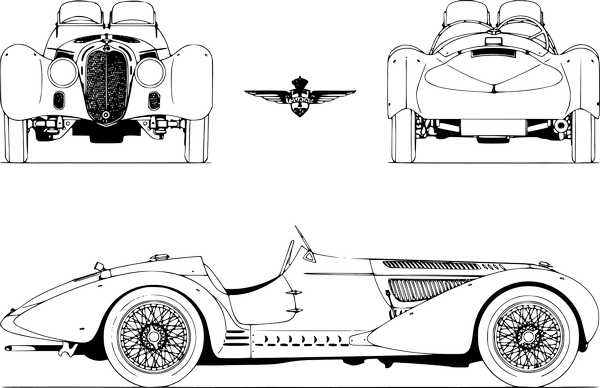

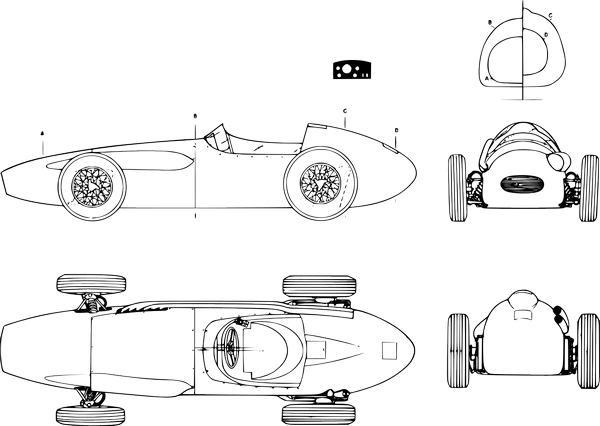

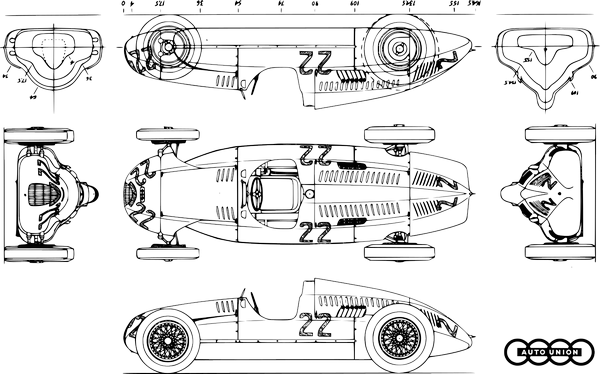

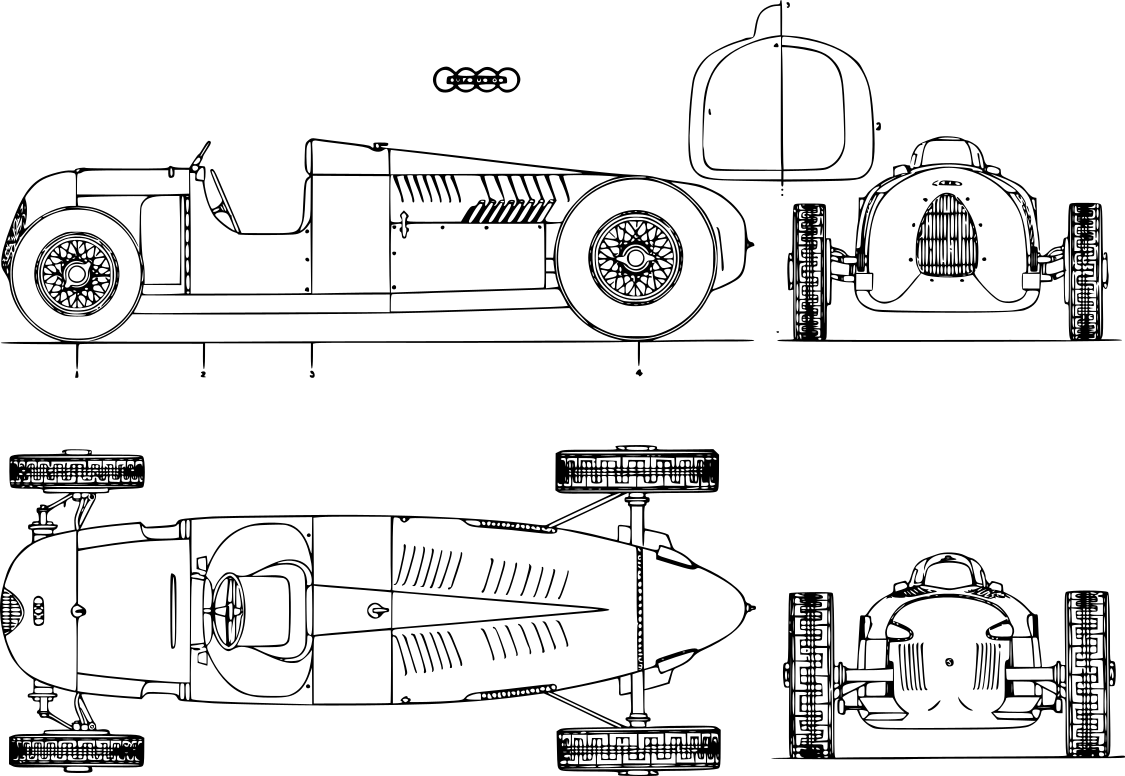

Scale Plan No. 4 | Model Car & Track July 1964 | Drawn & described by Jonathan Thompson

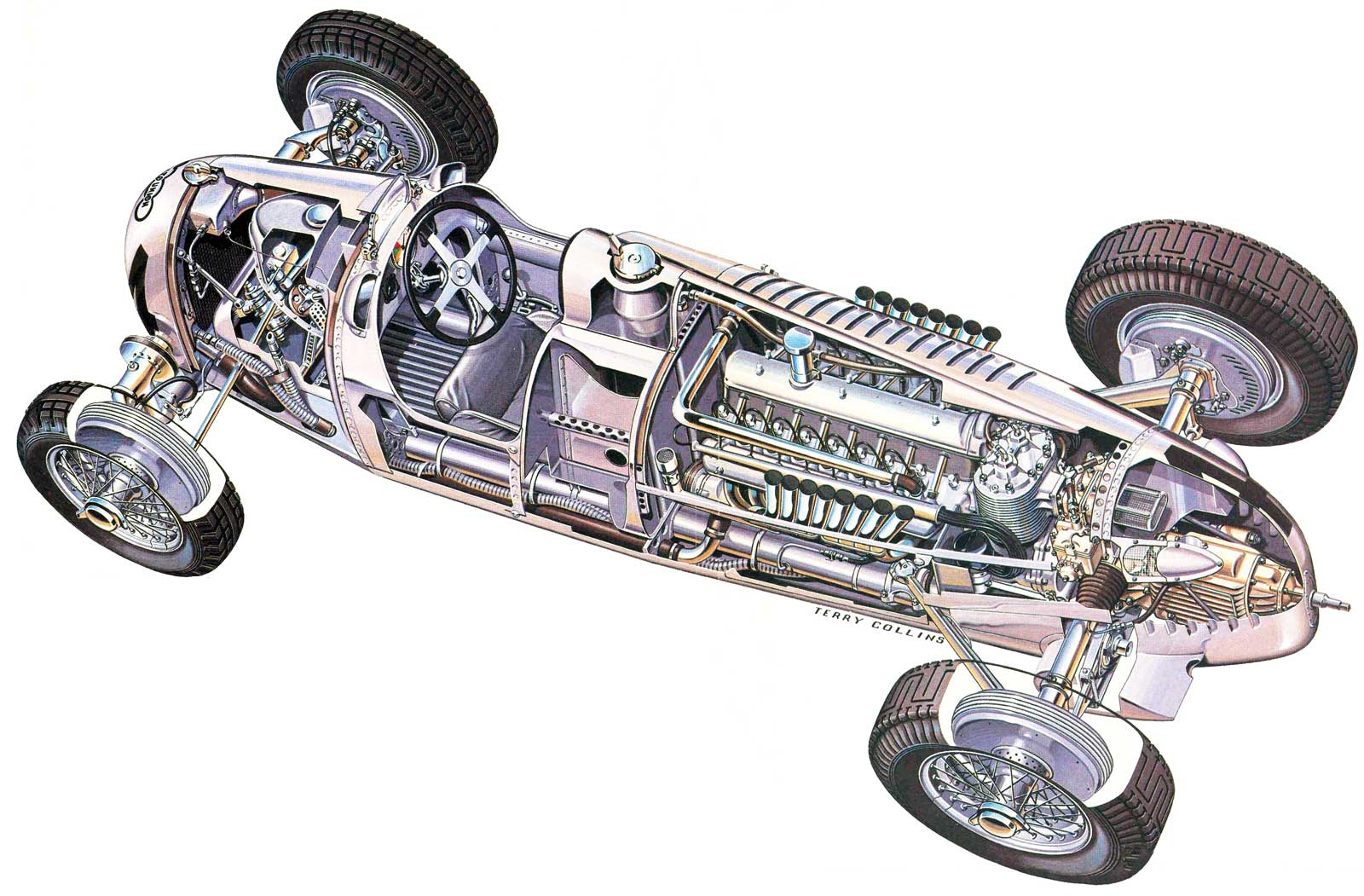

The only major change was a steady increase in the displacement and power output of its rear-mounted V16 engine, as follows: 1934 Typ A — 4360 cc/295 b.h.p.; 1935 Typ B — 4950 cc/375 b.h.p.; 1936-37 Typ C — 6006 cc/520 b.h.p.

During 1934-35 the Auto Unions were close competitors of the Mercedes-Benz W.25/25B; in 1936 the Typ C driven by Bernd Rosemeyer almost completely dominated the Grand Prix scene, much to the disgust of the Mercedes technicians, who were having nothing but trouble with their car, the handling being particularly bad. In 1936 Auto Union won the Tripoli, German, Swiss, and Italian grands Prix, as well as the Eifelrennen and the Coppa Acerbo. The Zwickau firm had bested Mercedes in five of eight encounters, although Tazio Nuvolari defeated Auto Union on four occasions with his Alfa Romeo! In 1937 the completely redesigned Mercedes-Benz W.125 regained the advantage for Stuttgart, but it must be pointed out that Auto Union had considerably less in terms of financial resources and capacity for research.

The Porsche machines were as a result less highly stressed; the design was expected to serve longer than the Mercedes (revised yearly), and in the case of individual cars to run in more races without major attention (the Mercedes cars were usually thoroughly rebuilt after two or three events). Thus the accomplishments of Auto Union are all the more praiseworthy.

Much credit must of course be given to Bernd Rosemeyer (one of the three truly great prewar Grand Prix drivers along with Tazio Nuvolari and Rudolf Caracciola), whose driving was really incredible. It has often been stated that only Rosemeyer, and later Nuvolari, could handle the reputedly vicious and undisputedly oversteering Auto Unions, but in fact the cars were also very well driven by Hans Stuck, Achille Varzi, and Hermann Muller. Rosemeyer was simply the only consistently first class driver Auto Union possessed, while Mercedes-Benz had the services of Caracciola, Manfred von Brauchitsch, Richard Seaman, and Hermann Lang, any one of whom might well have taken the Auto Union in stride had he found himself in the rival team. It might also be mentioned that it is relatively difficult to assess form during this period, when many accidents, retirements, and low placings were the result of burst tires, almost unknown in racing today.

For the new 3-liter formula commencing in 1938 Auto Union had a new car in the works, but the death of Rosemeyer in February of that year during a record breaking attempt caused the firm to give serious thought to retirement from racing. Muller, Rudi Hasse, and Christian Kautz had been signed, however, and the development of the new car was continued. Dr. Porsche had left the company, the design being that of Director Werner, Ing. Feureisen, and Prof. Dr. Ing. Eberan von Eberhorst.

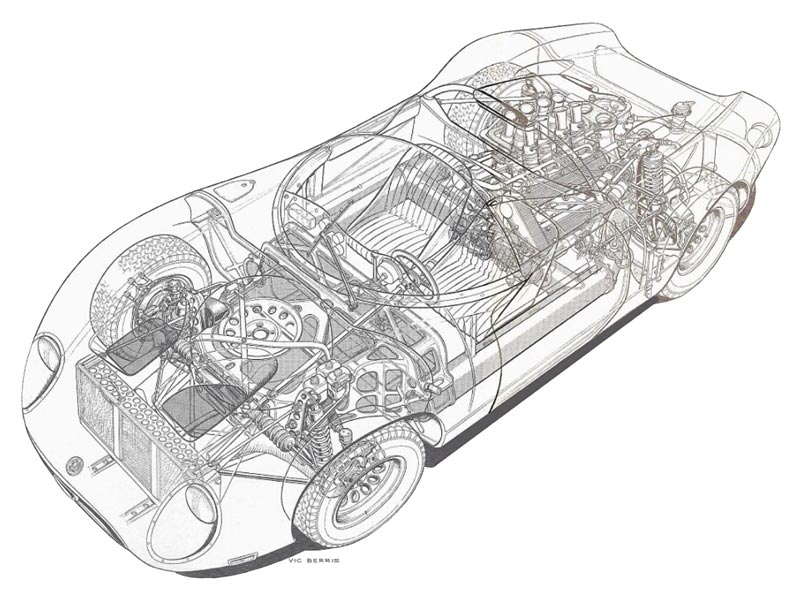

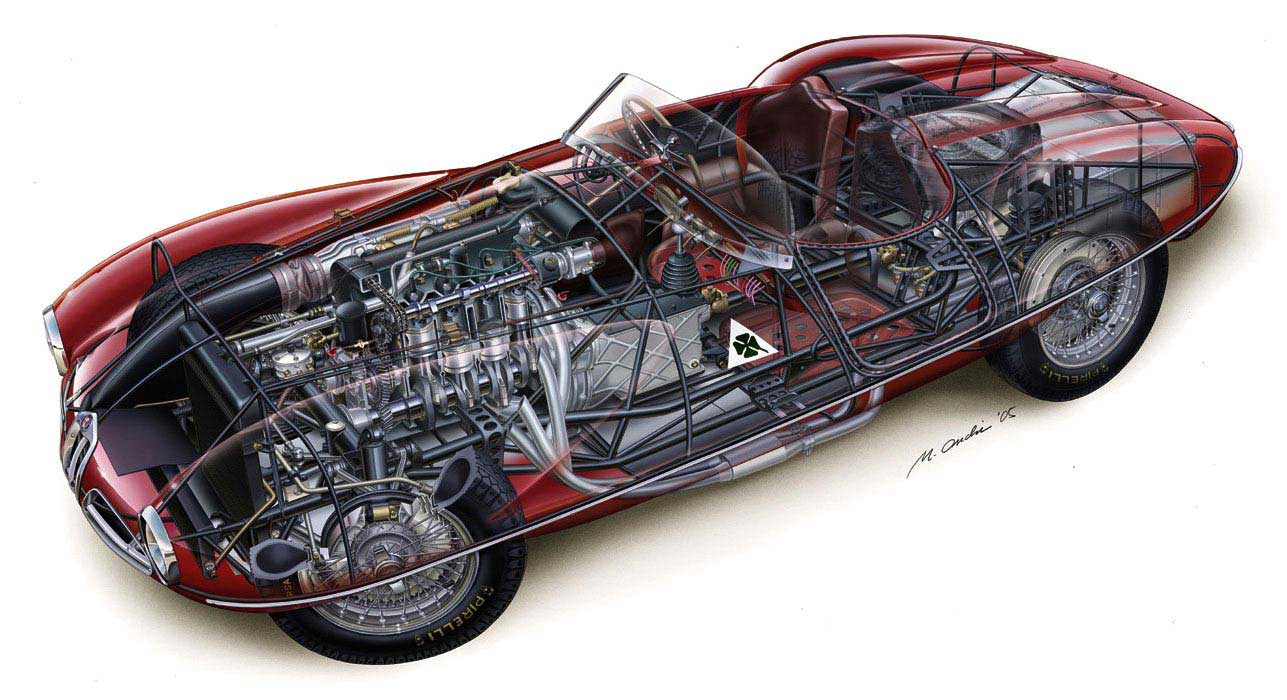

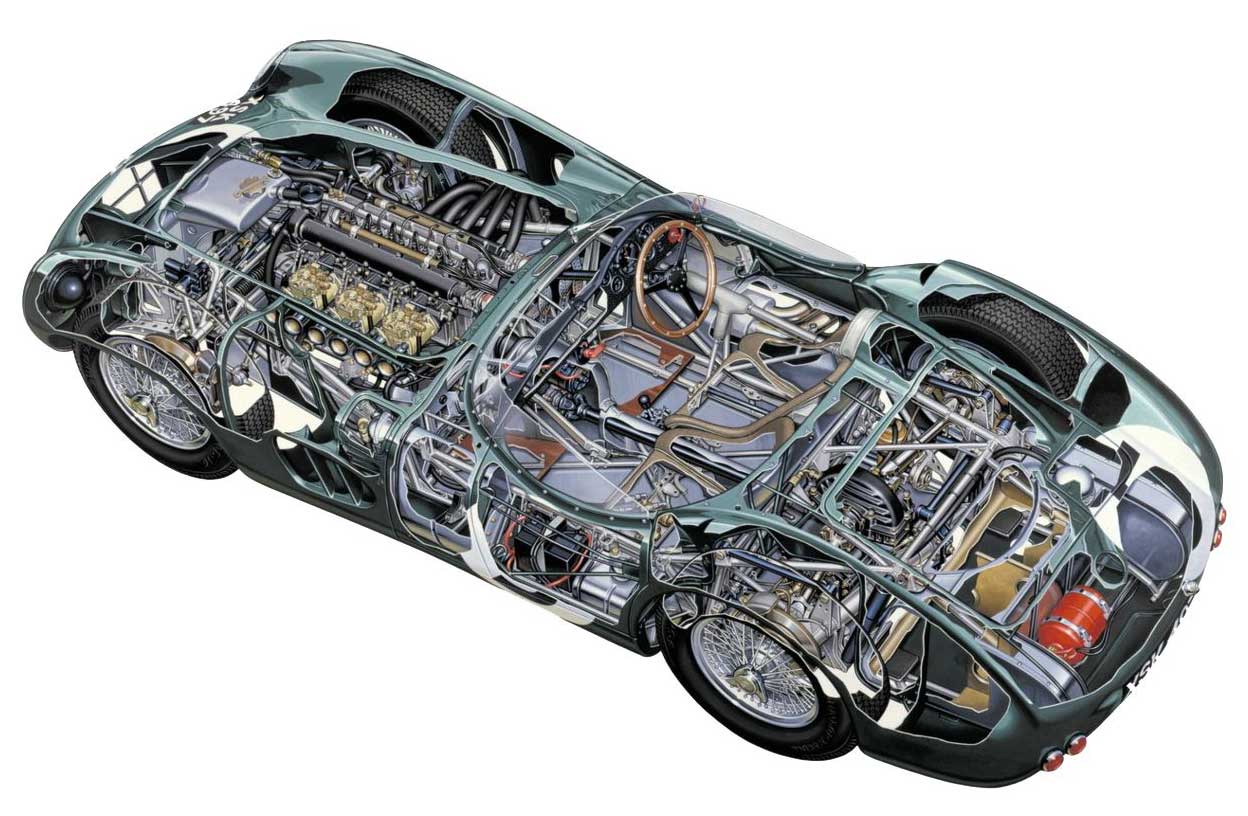

Although another V16 was rumored, the engine turned out to be a single stage supercharged 3-liter V12 with three camshafts, one between the cylinder blocks operating the intake valves and two operating the exhaust valves. Output was initially 420 b.h.p. at 7000 r.p.m. (compared with 520 b.h.p. at 5000 r.p.m. for the 6-liter V16). The chassis retained the Auto Union features, although the wheelbase was reduced from 114.5 inches to 108.2 inches, the steering geometry improved, and a de Dion rear end employed. The 5-speed gearbox and Z.F. limited slip differential were essentially the same, front suspension was again by transverse torsion bars and trailing arms, and the central fuel tank position was kept. On the 1938 car, however, this consisted of two side tanks connected by a central filler behind the driver (total capacity 60 Imp. gallons). This change plus the shorter engine allowed the driver's seat to be moved back substantially on the frame. The new driving position (along with the steering and suspension modifications, which changed the car from oversteering to inherent understeering characteristics) contributed to a great improvement in handling.

Despite the reduction in wheelbase, track, and engine displacement, the all-up weight of the car (2816 lb.) was actually greater by approximately 300 lb. than the older "big" car. Frontal area with the early 1938 body was also up from 10.8 to 11.5 sq. ft., and specific fuel consumption increased from about 4 m.p.g. to about 3 m.p.g. (which accounted for the large fuel capacity, 33 per cent greater than that of the 6-liter's 46 Imp. gallons). All of these changes, coupled with the reorganization of the design staff and the delay following the death of Rose-Meyer, set the appearance of the new car back several months. The car was tested at Monza in March, but due to various troubles it missed the Tripoli race and was not even ready for the Eifelrennen (subsequently cancelled as a result). At Monza the car had appeared with 16 exhausts stubs protruding from the engine compartment, disguising the nature of the new engine!

The first official appearance of the cars was at Rheims in July. Two special streamlined cars (Stromlinienwagen) were driven in practice by Muller and Hasse, both of whom unfortunately crashed, the former putting himself in the hospital. The streamliners were similar in form to the record-breaking machines of 1936-37 but had the new Grand Prix chassis. The drag coefficient was a low 0.20, compared to about 0.60 for the standard body. Speeds were competitive with those of the W.154 Mercedes, but instability was so great that after the crashes the development of the aerodynamic cars was abandoned altogether.

Auto Union did not intend to start in the race (July 3), but Mercedes-Benz, which would have been deprived of any reasonable competition, prevailed upon them to run anyway. Hasse and Kautz came to the line in standard cars, which had an interim bodywork similar in form to that of the Typ C except for the side tank fairings. Kautz spun, stalled, and retired on the first corner, while Hasse got little further, hitting a bank and breaking the axle. Neither car recorded a lap! Manfred von Brauchitsch won for Mercedes at 101.30 m.p.h.

After Rheims Auto Union enlisted the two veterans Louis Chiron and Hans Stuck to test the cars at the Nurburgring, the latter recording a respectable but not startling 10 min. 35 sec. On July 8 Nuvolari, who had left Alfa Corse after a frightening fire incident at Pau in an 8-cylinder Alfa Romeo 308, arrived at the Eifel mountain circuit to begin some fast practice in the German car, eventually clocking 10 min. 3 sec. (Brauchitsch had recorded 9 min. 49 sec. in a Mercedes).

Nuvolari signed with the team, beginning with the German Grand Prix on July 24. Driving a new car with revised 37 bodywork, he followed Lang closely at the start, but was soon passed by Caracciola and ended up off the road after a momentary slip on the second lap. Stuck finished third in the other new Auto Union, while Nuvolari took over Muller's earlier model to finish fourth. Hasse, driving another "old" model, retired with engine failure. The race was a triumph for Dick Seaman in a Mercedes at 80.75 m.p.h. after a fire in the pits ruined Brauchitsch's chances for almost certain victory.

The new Auto Union bodywork was considerably more rounded and graceful than that of the cars which had run at Rheims. Although the frontal area was increased slightly to 11.8 sq. ft. the drag coefficient was markedly reduced, particularly by the lower cowl and extended tail. Radiator air was ducted out the sides of the car behind the front wheels.

Still not satisfied with the cars, Auto Union passed up the Coppa Ciano (at Nuvolari's favorite circuit, Livorno) and appeared next at Pescara for the Coppa Acerbo, August 14. Four cars were entered for Nuvolari, Muller, Hasse, and Kautz, the last two driving the earlier models. Nuvolari encouragingly set the fastest lap in practice, but all four Auto Unions retired from the race, as did Lang and Brauchitsch in their Mercedes. Rudi Caracciola finished first in the sole remaining German car at an average speed of 83.69 m.p.h., followed by Giuseppe Farina in an Alfa Romeo.

The following week (August 21) saw the team at Bern for the Swiss Grand Prix. Nuvolari did some fairly fast times in practice but was not particularly happy with the car, while both Muller and Stuck went very fast. The race occurred in pouring rain. Stuck made a good start but the Auto Unions were not really competitive, being further hampered by plugs oiling up. Muller ran well in third place until near the end when he struck a tree and tore the rear end off his car. Stuck finished fourth, Nuvolari ninth (!), while Kautz retired the fourth machine after plug and carburetor troubles. Once again victory went to Caracciola (a master in the rain) at 89.44 m.p.h.

Auto Union finally scored in the Italian Grand Prix at Monza on September 11. Tazio Nuvolari delighted the Italian crowd with his superb driving and a convincing victory at an average speed of 96.70 m.p.h. The cars of Muller, Stuck, and Kautz retired, but so did the Mercedes of Brauchitsch, Seaman, and Lang. Caracciola ,had one of his very rare off course excursions, but the car finished third driven by Brauchitsch. The Italians were further pleased by the second place Alfa Romeo V16 of Farina. Lang led Nuvolari for eight laps but once the little Italian got by he took complete charge of the race. Except for a brief drop to second after a pit stop for tires and fuel, he led to the finish.

The Donington Grand Prix was originally to have been held the first week in October, but the Munich crisis caused it to be delayed until the 22nd. Nuvolari was again in great form, recording 2 min. 11.2 sec. in practice after hitting a stag! Only Lang beat this time (by 0.2 sec.). In the race Nuvolari took an immediate lead, followed by Muller, four Mercedes, and Hasse and Kautz in the other two Auto Unions. Kautz retired early after two spins. Nuvolari soon had an advantage of 21 sec., while Muller continued to hold off Seaman's Mercedes-Benz. Muller gained the lead when Nuvolari stopped for a plug change, dropping to fourth. Hasse's Auto Union left the road backwards after spinning on some oil, followed shortly after by Seaman. This advanced Nuvolari to third, behind Lang.

The German driver had his turn in front when Muller came in to refuel, and Nuvolari, driving ever faster, passed his teammate to lie second, 21 sec. behind Lang. On the 43rd lap Nuvolari broke the record in 2 min. 14.4 sec. and was now only 12 sec. behind the Mercedes. This he made up in four laps to take the lead and his second consecutive victory for Auto Union. Muller finished fourth. Auto Union could be proud of this conclusion to the 1938 season; although two cars had retired, it was through driver error in the case of Kautz and just plain misfortune with Hasse. Nuvolari's wining average was 80.49 m.p.h.

The team went to Monza again in March 1939 for early season training. The 1939 Auto Union differed little from the previous year, although a portion of the radiator air flow was ducted out louvers in the top of the hood, while the intake was smaller and the side exits partly shrouded to improve aerodynamics.

The first race of the season for Auto Union was the Eifelrennen, held at the Nurburgring on May 21. In practice Nuvolari tied for second fastest with Caracciola at 9 min. 57 sec., Lang being the quickest at 9 min. 54 sec. Lang went even faster in the race, and took first place at an average speed of 84.15 m.p.h., while Nuvolari came in second after a non stop drive. The Continental tire technicians had advised him not to try to go the whole distance on one set of tires, but at the end he still had enough rubber for another lap. All the Auto Unions finished, although the remainder were in relatively low positions, Hasse being fifth, Bigalke (a new team member) sixth, and Muller seventh. The Eifelrennen was only ten laps (a "sprint" race) compared to 22 laps for the German Grand Prix on the same circuit.

The tragic Belgian Grand Prix, run at Spa on June 25, saw the death of Dick Seaman, who crashed in the rain while leading. The Auto Unions were never a strong challenge, although Nuvolari was as high as third before going off the road. Georg Meier, another new Auto Union pilot, had also crashed, and Muller retired as well. Rudi Hasse did well to finish second, one lap behind Lang, who won at an average of 94.39 m.p.h. and net the fastest lap at 101.35 m.p.h. On the same day Hans Stuck achieved hollow victory for Auto Union at Bucharest, Rumania, there being no significant opposition.

The French Grand Prix was held at Rheims on July 9. It could not have been more different from the race of the previous year, Auto Union and Mercedes fortunes being completely reversed. The 39 circuit had been improved and speeds increased considerably; Lang did 117.5 m.p.h. in practice and Nuvolari was also in the front row with 116 m.p.h. Both Nuvolari and Muller had new two stage supercharged cars, distinguished by external air intakes on the right side of the engine compartment leading to a bulge at the back. Power output was 485 b.h.p., although over 500 b.h.p. was recorded briefly.

Nuvolari led off with a standing first lap average of 115 m.p.h., while Lang was right behind him. Caracciola had already crashed on the first lap! Nuvolari stayed ahead for eight blistering laps before his Auto Union blew up. Lang took over the lead but both he and Brauchsitch eventually retired, leaving Auto Union a one-two victory. Muller was first at 105.25 m.p.h., followed by Meier a lap behind. Although Lang had set the fastest lap, no Mercedes finished.

Caracciola and Mercedes-Benz got their revenge at the Nurburgring on July 23. He averaged 75.18 m.p.h. in scoring his sixth German Grand Prix victory and also set the fastest lap at 81.66 m.p.h. Muller finished second with a two stage Auto Union, while Nuvolari and Stuck retired in similar machines. Hasse and Meier, in older single stage cars, also failed to complete the course.

The Swiss Grand Prix (August 20) was run in two heats and a final, the first heat for voiturettes (1500 cc), the second for the big cars, and the final for both. Lang won the second heat and the final, although the first heat winner, Farina's Alfa Romeo 158, turned in an amazing performance. Farina held second for six laps and eventually finished sixth. Two Auto Unions came in fourth and fifth (Muller and Nuvolari, respectively); Hasse and Stuck retired. Lang's winning average was 96.02 m.p.h., although Caracciola put in the fastest lap at 104.32 m.p.h.

The last race of the dramatic prewar period, and the final race for Auto Union, was the Belgrade Grand Prix held in Yugoslavia on September 3, coinciding with the outbreak of the Second World War. Two Auto Unions (Nuvolari and Muller) faced three Mercedes (Lang, Brauchitsch, and Baumer). Although Lang and Brauchitsch led in turn, the former blew up and the latter spun, letting Nuvolari into the lead which he held to the end. Muller finished third.

The Auto Union Typ D was slow to be developed in 1938 and was outpaced in 1939 by the Mercedes-Benz W.163, but it won four major races and one minor event, scored four second places and two thirds. The Auto Union V12 produced slightly more power than its rival (485 b.h.p. compared with 483 b.h.p. for the W.163); in addition, both weight and frontal area were less. Both cars, properly geared, could achieve 195 m.p.h. Nevertheless, the cars from Stuttgart were nearly always faster around the circuits than the Auto Unions, except when Nuvolari was really going fast!

Had Auto Union possessed second and third string drivers of the caliber of Lang and Brauchitsch, plus a more efficient organization, the races of 1938-39 would have been even more closely fought. At any rate, the Porsche designed rear engined machines set the style for the Grand Prix cars we know today, although it took the rest of the racing car manufacturers more than tvventy-five years to catch on!

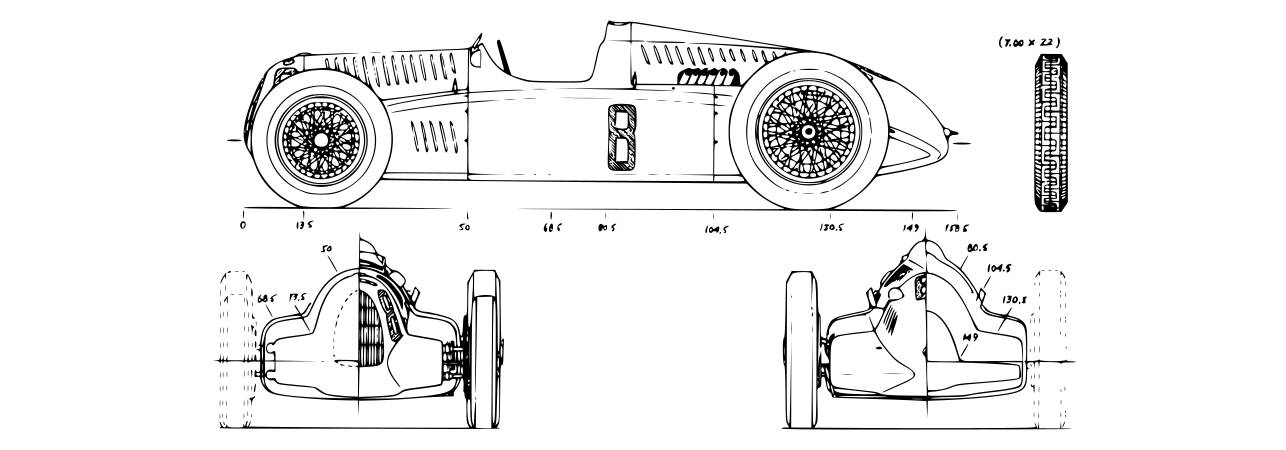

SPECIFICATIONS: Engine, 90-degree V12; three gear-driven overhead camshafts (one intake, two exhaust); single-stage (later two-stage) Roots supercharger driven from rear end of crankshaft; 65 x 75mm., 2990 cc; 420 b.h.p. (later 485 b.h.p.) at 7000 r.p.m., 140.4 (162.2) b.h.p.1 liter; compression ratio 10/1. Three-plate clutch in oil. Transmission, 5-speed all-indirect gearbox in unit with Z.F. limited-slip differential. Tubular steel frame. Front-mounted radiator and oil cooler. Front suspension, Porsche parallel-action trailing arms with transverse torsion bars and double-acting hydraulic shock absorbers. Rear suspension, de Dion with Panhard rod for lateral location, longitudinal torsion bars and double-acting friction shock absorbers. Fuel capacity, 60 Imp. (71 U.S.) gallons. Brakes, 4-leading shoe hydraulic drum type, 15.75-inch diameter. Rudge detachable wire wheels. Tires, Continental 5.25 x 19 front, 7.00 x 19 rear, or for fast circuits, 5.50 x 19 front, 7.00 x 22 rear.

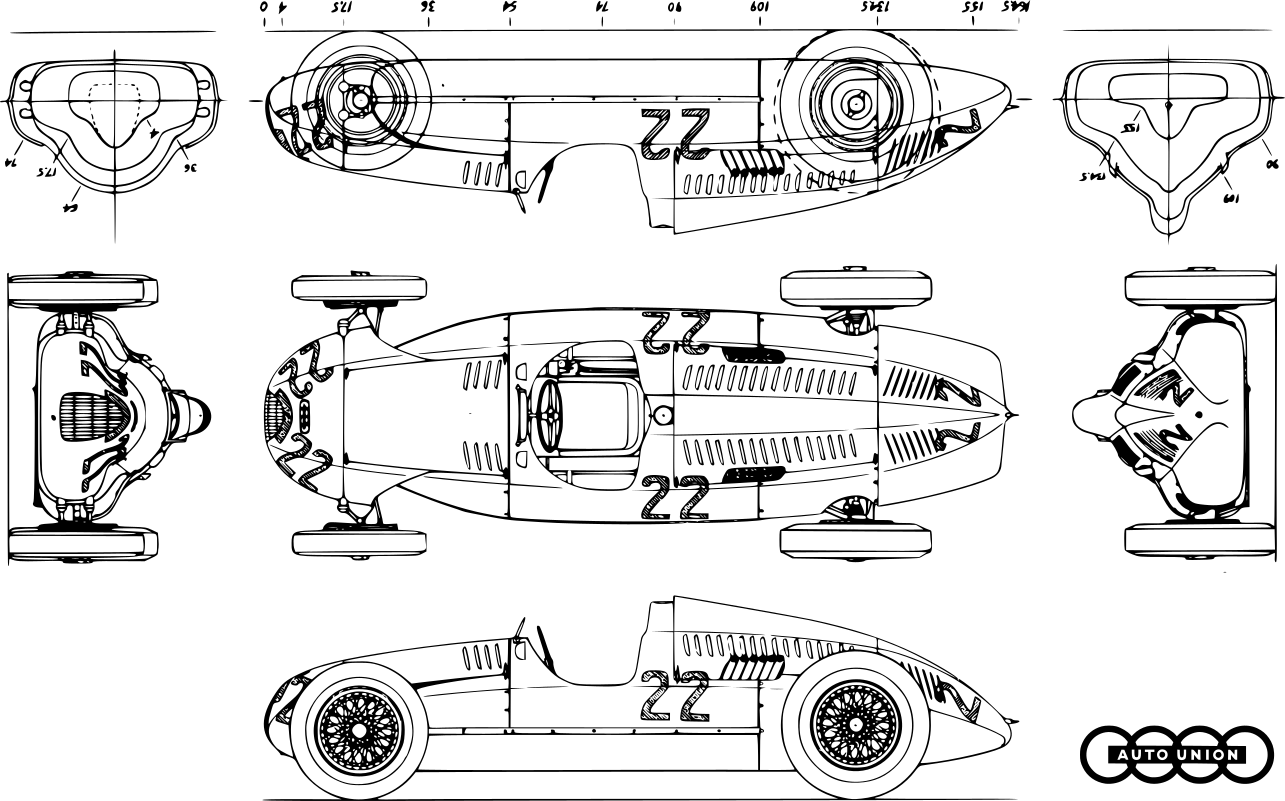

DIMENSIONS: Wheelbase 108.2 inches. Track 55.1 inches, front and rear. Ground clearance 3 inches. Weights, 1938 lb. dry, 2816 lb. with fuel (568 lb.), oil (70 lb.), water (65 lb.), and driver (175 lb.).

BODY DIMENSIONS, Reims

streamliner: Length 201.0 inches. Width 74.9 inches. Height (cowl) 36.8 inches. Height (headrest) 44.0 inches. Frontal area 15.7 sq. ft. Early. 1938 car: Length 158.5 inches. Width 45.0 inches. Height (cowl) 36.8 inches. Height (headrest) 41.8 inches. Frontal area 11.5 sq. ft. 1938-39 car: Length 164.5 inches. Width 47.5 inches. Height (cowl) 35.5 inches. Height (headrest) 44.3 inches. Frontal area 11.8 sq. ft.

COLORS: Bodywork, silver (polished aluminum). Seat, beige. Numbers, red. Auto Union device, black.

CAR NUMBERS: Reims 1938: Hasse 16, Kautz 20 Nurburgring 1938: Nuvolari 2, Stuck 4, Hasse (old type) 6. Muller (old type) 8. Pescara 1938: Muller 30, Nuvolari 40, Hasse (old type) 44 Bern 1938: Nuvolari 6, Stuck 8 Monza 1938: Muller 20, Nuvolari 22 (red nose band) Donington 1938: Muller 1, Hasse 2, Kautz 3, Nuvolari 4 Nurburgring (Eifelrennen) 1939: Nuvolari 2, Muller 6 Reims 1939: Muller 14,Nuvolari 8 Nurburgring (G.P.) 1939: Nuvolari 2, Stuck 4, Muller 6, Hasse 8, Meier 10 Bern 1939: Nuvolari 2, Muller 6