26th-Mar-22, 05:50 PM

Sample Navigation – from head-scratching to tulips in just 40 junctions

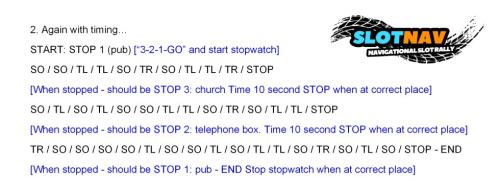

Driving a SlotNav rally route is not something you can successfully do on your own. Just to practice, you definitely need a driver and a navigator – and any competitive event will require a Rally Master to plan the route, time the runs and judge the navigation. In this post, I’ll demonstrate a simple 40-junction navigation (with two intermediate ‘reset’ stops) that I used in an early practice session, designed for me and my slightly-reluctant navigator to get used to the process...

Including the direction of each junction - Left or Right - might help the driver work out where they ought to be on the layout, but it is not essential. Definitely helpful for the learning process was having the extra (blue) text – that’s information for the Race Master and would normally be removed from the navigator’s instructions for a competition run. The blue text explains the reset at each Stop Box, so the crew know if they’re on the right route or have made an error somewhere.

One issue that analogue racers might have – and digital racers aren’t immune from – is that the lane-change sensor is situated about a foot before the visible turn. The lane-change button needs to be pressed before the sensor is reached and then held. It’s a process that needs practice to get as smooth and reliable as possible...

Starting with no idea what we were doing, we gradually worked out a method that suited us both: my navigator read an instruction – either ‘Turn Right’, ‘Turn Left’ or ‘Straight On’ – and I said ‘Yes’ when I was ready for the next one. Some junctions are closer together than others, so that allowed me to get the info exactly when I needed it – not too soon or too late. We also discovered that the Stop command should be tagged onto the final instruction – so ‘Turn Right – STOP’. My navigator also crossed out each instruction when it was given, to help keep her place on the navigation sheet.

Until we got in a good flow, I had to stop the car quite frequently to wait for an instruction – usually because I’d forgotten to say ‘Yes’. And I missed a few turns by being late on the lane-change button – I then simply did a loop and took the junction correctly. However, it was a reassuringly gentle learning-curve for both driver and navigator – and after three untimed runs through the route, we raced against the clock...

The first timed run was a bit of a nervous 2 minutes 50 seconds. Here’s a video of that run – with lots of “Yeses” which do sound decidedly weird out of context!

Despite some obvious pauses and one missed turn, our communication was improving and my driving speed gradually increased too. After a couple more runs, we eventually stopped the stopwatch at 2 minutes 11 seconds. That time includes two 10 second stops, so a running time of 111 seconds to cover 40 junctions – that’s an average of one junction every 2.8 seconds… and I’m sure we could have gone faster.

Depending on the rally format you’re attempting to re-create, there are ways to keep that rapid-fire stream of junctions manageable. Setting a minimum time or a target time is one way. That requires either a reasonably proficient crew to set a time through the route – or to decide on a standard average time per junction, let’s say 3 seconds. In a competition, any crew arriving at a time control before the minimum time is either awarded that minimum time or gets handed a penalty. Perfect navigation should be preferable to a mega-fast time with errors. Any format can be tweaked to reward that.

Next, we tried the same simple route using a set of basic Tulip symbols, which also give detailed information about the type of junction/lane-changer…

This was a new skill for the navigator, but one that she picked up very quickly. Of course, I received the same instructions – ‘Turn Left’, ‘Turn Right’ or ‘Straight-On’ – and I didn’t notice any difference at all. We completed the same route as before in 2m 23s.

Skill progression for the co-driver is probably the key element of navigational rallying – both in real life and on the slot car track. From Tulips, the navigator can move on to Herringbones, Ordinance Survey maps and more... For an idea of different navigational instructions and how a Rally Master might use them, ‘Percy’s Guide to 12-Car Navigation’ is a great start: http://www.sccon.co.uk/share/pprns/SCCoN...ide_v3.pdf

After these first runs, we tried a few different techniques – for example, reading two junctions at a time worked really well... but might have been tricky to begin with and probably risks more errors from the driver. Ultimately, success was down to good teamwork, clear communication, following the instruction sheet carefully and not trying to be clever – plus lots of practice!

It also became clear that the navigator should focus entirely on the navigating and the driver deals with de-slots, a quick clean of tyres at the Stop box halts – plus navigating back to any missed junctions. Driving was a bigger job that I’d anticipated – trying to go fast was the last thing on my mind.

We worked up to a longer route – 87 junctions, split into five sections with three intermediate stops…

That took a second under six minutes – or 329 seconds running time, without the Stop Box pauses – meaning a junction every 3.7 seconds, on average. The slickness of our navigation did ebb and flow, but we reached the correct Stop Box each time. I reckon a route that takes around six minutes feels like a real test of concentration – although the short two minute route was perfect to begin with. That means an ideal competitive route on my development track might be somewhere between 80 and 120 junctions in length. However, that decision is down to the Rally Master, to whom the final two posts are dedicated...

You'll have to wait until tomorrow for those - but you do have enough info already to set up a track and practice that basic navigation.

Driving a SlotNav rally route is not something you can successfully do on your own. Just to practice, you definitely need a driver and a navigator – and any competitive event will require a Rally Master to plan the route, time the runs and judge the navigation. In this post, I’ll demonstrate a simple 40-junction navigation (with two intermediate ‘reset’ stops) that I used in an early practice session, designed for me and my slightly-reluctant navigator to get used to the process...

Including the direction of each junction - Left or Right - might help the driver work out where they ought to be on the layout, but it is not essential. Definitely helpful for the learning process was having the extra (blue) text – that’s information for the Race Master and would normally be removed from the navigator’s instructions for a competition run. The blue text explains the reset at each Stop Box, so the crew know if they’re on the right route or have made an error somewhere.

One issue that analogue racers might have – and digital racers aren’t immune from – is that the lane-change sensor is situated about a foot before the visible turn. The lane-change button needs to be pressed before the sensor is reached and then held. It’s a process that needs practice to get as smooth and reliable as possible...

Starting with no idea what we were doing, we gradually worked out a method that suited us both: my navigator read an instruction – either ‘Turn Right’, ‘Turn Left’ or ‘Straight On’ – and I said ‘Yes’ when I was ready for the next one. Some junctions are closer together than others, so that allowed me to get the info exactly when I needed it – not too soon or too late. We also discovered that the Stop command should be tagged onto the final instruction – so ‘Turn Right – STOP’. My navigator also crossed out each instruction when it was given, to help keep her place on the navigation sheet.

Until we got in a good flow, I had to stop the car quite frequently to wait for an instruction – usually because I’d forgotten to say ‘Yes’. And I missed a few turns by being late on the lane-change button – I then simply did a loop and took the junction correctly. However, it was a reassuringly gentle learning-curve for both driver and navigator – and after three untimed runs through the route, we raced against the clock...

The first timed run was a bit of a nervous 2 minutes 50 seconds. Here’s a video of that run – with lots of “Yeses” which do sound decidedly weird out of context!

Despite some obvious pauses and one missed turn, our communication was improving and my driving speed gradually increased too. After a couple more runs, we eventually stopped the stopwatch at 2 minutes 11 seconds. That time includes two 10 second stops, so a running time of 111 seconds to cover 40 junctions – that’s an average of one junction every 2.8 seconds… and I’m sure we could have gone faster.

Depending on the rally format you’re attempting to re-create, there are ways to keep that rapid-fire stream of junctions manageable. Setting a minimum time or a target time is one way. That requires either a reasonably proficient crew to set a time through the route – or to decide on a standard average time per junction, let’s say 3 seconds. In a competition, any crew arriving at a time control before the minimum time is either awarded that minimum time or gets handed a penalty. Perfect navigation should be preferable to a mega-fast time with errors. Any format can be tweaked to reward that.

Next, we tried the same simple route using a set of basic Tulip symbols, which also give detailed information about the type of junction/lane-changer…

This was a new skill for the navigator, but one that she picked up very quickly. Of course, I received the same instructions – ‘Turn Left’, ‘Turn Right’ or ‘Straight-On’ – and I didn’t notice any difference at all. We completed the same route as before in 2m 23s.

Skill progression for the co-driver is probably the key element of navigational rallying – both in real life and on the slot car track. From Tulips, the navigator can move on to Herringbones, Ordinance Survey maps and more... For an idea of different navigational instructions and how a Rally Master might use them, ‘Percy’s Guide to 12-Car Navigation’ is a great start: http://www.sccon.co.uk/share/pprns/SCCoN...ide_v3.pdf

After these first runs, we tried a few different techniques – for example, reading two junctions at a time worked really well... but might have been tricky to begin with and probably risks more errors from the driver. Ultimately, success was down to good teamwork, clear communication, following the instruction sheet carefully and not trying to be clever – plus lots of practice!

It also became clear that the navigator should focus entirely on the navigating and the driver deals with de-slots, a quick clean of tyres at the Stop box halts – plus navigating back to any missed junctions. Driving was a bigger job that I’d anticipated – trying to go fast was the last thing on my mind.

We worked up to a longer route – 87 junctions, split into five sections with three intermediate stops…

That took a second under six minutes – or 329 seconds running time, without the Stop Box pauses – meaning a junction every 3.7 seconds, on average. The slickness of our navigation did ebb and flow, but we reached the correct Stop Box each time. I reckon a route that takes around six minutes feels like a real test of concentration – although the short two minute route was perfect to begin with. That means an ideal competitive route on my development track might be somewhere between 80 and 120 junctions in length. However, that decision is down to the Rally Master, to whom the final two posts are dedicated...

You'll have to wait until tomorrow for those - but you do have enough info already to set up a track and practice that basic navigation.

![[+]](https://slotracer.online/community/images/bootbb/collapse_collapsed.png)