Fuji Speedway

1976. Fuji. Hunt. Lauda.

Those words are probably enough to send a shiver of excitement down the spine of anyone who followed Formula One back in the day. If you were one of those people, then the memories of the whole of the 1976 season have likely come flooding back at the thought of that final race, the fascinating, nail biting climax to a tumultuous season.

There was just so much to savour during the season, not least of which were the contrasting characters and fortunes of the two main protaganists. On the one hand there was the studious Austrian World Champion who fought back bravely from life threatening injuries to challenge for a second world championship. On the other was the tall, blonde and charismatic Englishman who proclaimed that sex was the breakfast of champions.

The story of the 1976 season has an incredible resonance for motorsports fans, but went beyond the confines of sport, and into the wider realms of human drama. Perhaps uniquely, both Lauda and Hunt elevated themselves to greatness during that unforgettable season, but only one man was able to hold aloft the world champion’s trophy at the end of the year.

Great Sporting Moments

The Independent | 14 July 2009 | David Tremayne

James Hunt scowled at the angry clouds that hid Mount Fuji, then at the sodden racetrack on which the 1976 Japanese grand prix would decide a world championship that seemed to have come from a Hollywood B-movie plot.

"I would rather give Niki the title than race in these conditions," he declared.

He and Niki Lauda, the Austrian world champion, had duelled their way across the world that year, Lauda in his Ferrari, Hunt leading the McLaren team. In a season scarred by protests, disqualifications and controversy, the two close friends had shared most of the victories: Lauda in Brazil, South Africa, Belgium, Monaco and Britain (where Hunt was disqualified); Hunt in Spain, France, Germany, Holland, Canada and America.

Hunt v Lauda

Then, on 1 August, Lauda's Ferrari crashed violently in the German GP on the old Nurburgring. Dragged from the flaming wreckage by fellow drivers Guy Edwards, Arturo Merzario, Brett Lunger and Harald Ertl, Lauda lingered between life and death after inhaling smoke and poisonous gases.

Drawing on all the force of will that would become part of his legend, Lauda not only survived but astonished doctors with the speed of his recovery.

Sensationally, on 12 September, he fought his way to a fourth place finish in the Italian grand prix behind Ronnie Peterson, Clay Regazzoni and Jacques Laffite.

His head was still swathed with blood-soaked bandages and his mind was in turmoil. "At Monza, I hid the truth. I'd never been as scared as I was then. I was rigid with fear. Terrified. Diarrhoea. Heart pounding. Throwing up."

In Lauda's absence, Hunt won in Holland and took fourth in Austria, was controversially penalised in Italy, then won both north American races, where Lauda was eighth and third.

And so their fight distilled into a three-point gap in Lauda's favour and a 73-lap showdown in Japan. And now, just to ratchet the tension up another notch, it seemed that speedboats would be more appropriate than racing cars.

There were several incidents in the soaking morning warm-up, as cars aquaplaned and spun, and the drivers were divided. Hunt, Lauda, Emerson Fittipaldi and Carlos Pace, stars all, were against racing and wanted a postponement. Ronnie Peterson, Vittorio Brambilla, Clay Regazzoni, Patrick Depailler, Hans Stuck and Alan Jones were all for driving. And then there was the Welshman Tom Pryce, the greatest of them all in the wet, who simply said: "We are supposed to be the best drivers in the world, so we should be able to race in the rain ..."

There were delays as the organisers held endless meetings and prevaricated. The pressure upon them was enormous. They had invested more than $1m in their race, and 80,000 spectators had paid handsomely to attend. Now, hunched beneath their umbrellas, all they had to watch was cars hidden beneath tarpaulins and small figures scuttling around in the pit road.

And there was another crucial imperative in favour of racing. The intensity of Hunt's battle with Lauda had captured imaginations. Now the world was hungry to know what was going to happen as their amazing fight went down to the wire. The 1976 Japanese grand prix was a ground-breaking affair, the event that would put Formula 1 permanently on global television's map.

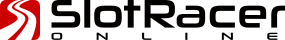

Fuji Speedway 1976

| 10105 | x4 |

| 10113 | x1 |

| 10104 | x1 |

| 10103 | x2 |

| 10102 | x17 |

| 10115 | x14 |

| 10108 | x5 |

| 10107 | x4 |

| 10106 | x4 |

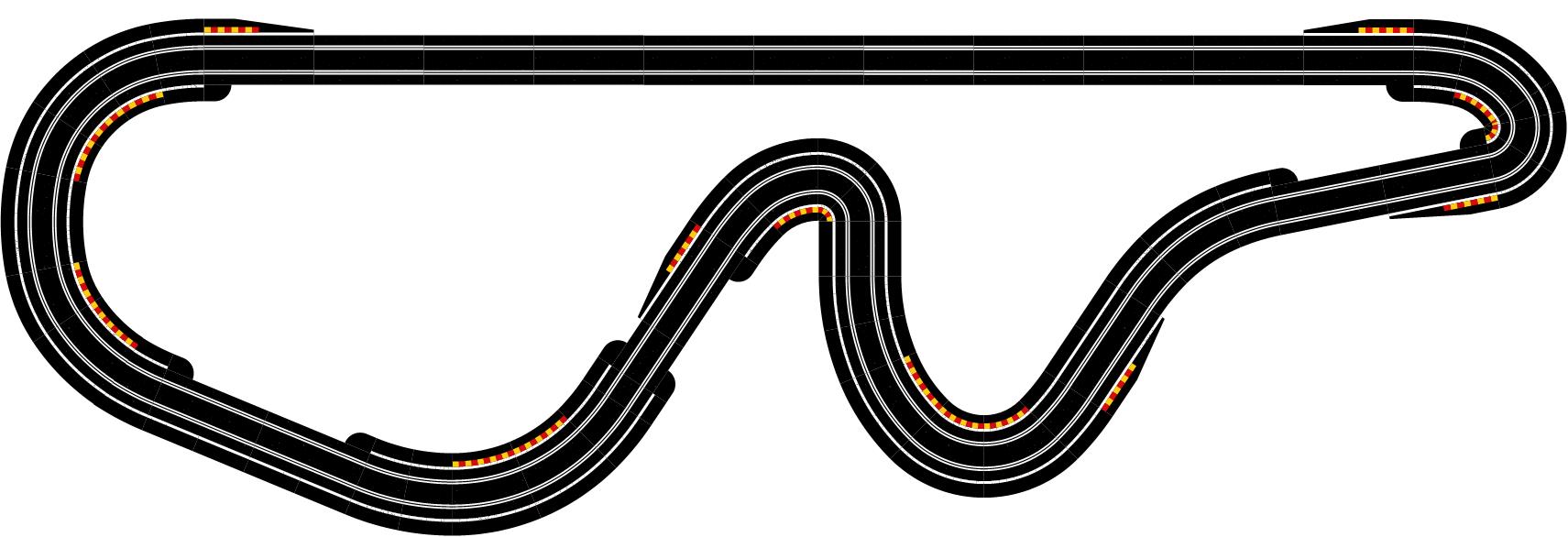

Fuji Speedway 1965-74

| 10105 | x9 |

| 10104 | x1 |

| 10103 | x6 |

| 10102 | x19 |

| 10115 | x20 |

| 10108 | x10 |

| 10107 | x8 |

| 10106 | x2 |

The Track

Fuji Speedway was originally planned as a NASCAR style oval. However, after completing the first of the two huge banked turns, financial constraints and a little advice from Stirling Moss, prompted a revision of the plans and the circuit was completed as a road course.

The circuit opened in 1965, and in spite of the changes, Fuji was still fearsomely fast. The long straight, almost a mile long, lead directly onto the banking, and unusually, the cars rose over the crest of a hill before dropping down into the banked right hander.

Several monumental accidents occurred in the early years, but the fate of the banking was sealed in 1974, when drivers Hiroshi Kazato and Seiichi Suzuki were both killed in a fiery accident which injured six other people. A new downhill hairpin bend was installed at the end of the main straight which bypassed the banking. This the configuraion that was used in the 1976 F1 GP, and the banking was never used again.

Great Sporting Moments

The Independent | 14 July 2009 | David Tremayne

Hunt sat on the front row of the grid, alongside the American Mario Andretti in a Lotus. Lauda was third, with the Austrian grand prix winner, John Watson, in a Penske, for company. Hunt was his usual tense self in the McLaren garage, retching with nerves as he so often did before a race.

When he was strapped into his brightly coloured red and white McLaren, and the signal to start the race was finally given, he told his crew very quietly: "I'm not going to race. I can't. I'm just going to drive round."

The moment it started, however, the racer in Hunt took charge. He made his best getaway of the season, and became the only man with clear visibility as he headed Watson and Andretti. At the end of that tense opening lap, he skated into the first corner, aquaplaned across a huge puddle as he braked from 140 mph, and barely retained control. Far from just driving round, he was going for it with all he had.

A lap later, his task became easier. To the astonishment of onlookers, Lauda trickled his Ferrari slowly into the pits. And stepped out.

Some called him a coward – this man who only weeks before had drawn praise for his incredible bravery. But not Hunt. "Poor Niki!" he said later. "In a perfect world, we would have shared the championship. He's been through a terrible accident and his comeback has been amazing. But I think he made the right decision to stop, and I feel awfully sorry for him. For me, Niki's decision was the bravest of all."

Initially, Hunt swept away, hydroplaning on his own tide of adrenalin. Watson, second initially, slid down the escape road in the first corner; Brambilla, moving up fast, destroyed his front left tyre within five laps and made a pit stop. Andretti moved up to chase the McLaren, but was supplanted again by the flying Brambilla on the 16th lap. Now McLaren were afraid: the "Monza gorilla" was an unpredictable fellow. As if the conditions were not tricky enough, Hunt now had to cope with somebody who could be fast and furious.

On the 21st lap, Brambilla caught Hunt but spun across his bows just as he took the lead. The March missed the McLaren by inches.

Now Hunt had his team-mate, Jochen Mass, on his tail. But then the German lost concentration after easing off in his shotgun riding role, and slid into a barrier. Hunt's cushion had gone. Worse still, the track was drying. The clouds had blown away, streaks of blue were visible in the sky. If he'd had time, Hunt could even have caught glimpses of Mount Fuji. But his wet weather tyres were in a parlous state. The drying track was literally tearing them apart, and there was still half the race to run.

In his cockpit, Hunt began to curse. Lap after lap, he sought direction from his crew. Should he pit for fresh tyres? But all he got was the signal that the decision was up to him. "I couldn't get a communication going with them," he said. "I didn't want to make the decision!"

On lap 62, Depailler and Andretti overtook him. Third place was still sufficient to clinch the title by a point from Lauda, but Hunt could feel his tyres were finished. There was momentary respite when Depailler's Tyrrell blew a tyre. But his own worst fears were realised three laps later when the same thing happened to his left front tyre. Now the decision to pit was made for him, and he dropped to fifth place behind Andretti, Regazzoni, Jones and Depailler. The championship was lost.

Clash of the Titans - Lauda v Hunt

Great Sporting Moments

The Independent | 14 July 2009 | David Tremayne

He drove his last three laps in a red mist. On his fresh wet weather tyres, he overtook both Regazzoni and Jones on the 71st lap, but had no idea himself where he was even as he finished third, a lap behind the victorious Andretti, who had nursed his tyres perfectly.

Even as delirious team members climbed on to the McLaren's sidepods as he drove in, Hunt would not be dissuaded from his belief that his team had just cost him the title.

Finally, it began to percolate what people were saying: "You're third, James! You've done it! You're world champion!" But still he took a lot of convincing. He had discovered more than once that year that the winner was not always the man who crossed the finish line first.

Later Hunt visited the press room, and gradually let his success sink in. But by then it was almost anti-climactic. "When I came out, it was pitch dark and everyone had gone," he remembered. "The place was deserted. I reckoned that even if anyone had wanted to do anything about talking the title from me, they couldn't be bothered. Nobody was interested. They'd had enough. I decided to accept it. I must be world champion."

Somehow, it was a fitting climax to a crazy year.